Malia Hunter

Student Production Dramaturg

DeRon S. Williams, Ph.D., Dramaturgy Supervisor

William Shakespeare

Playwright

William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language. He was born on or around 23 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, the eldest son of John Shakespeare, a prosperous glover and local alderman. There are no records of Shakespeare’s education, but he probably went to King’s New School – a reputable Stratford grammar school where he would have learned Latin, Greek, theology and rhetoric. Shakespeare also may have had a Catholic upbringing, considering his parents would have lived through the Reformation and may have held on to their old beliefs. In 1582, at 18 years of age, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, and the couple had three children over the next few years. Then, from 1587-1592, Shakespeare disappears from recorded history. Sometime during this period, he moved from Stratford to London and entered the theatre scene. The next mention of Shakespeare comes in 1592, when another playwright, Robert Greene, published a scathing attack on his writing. From this we can understand that by 1592, Shakespeare was already successful enough to have his plays well-known and his words quoted. Indeed, Shakespeare soon became so successful that he was able to purchase the second-largest house in Stratford by 1597, well before his career could be considered over. Shakespeare continued his prolific work throughout the first decade of the 1600s, but by 1610 it was apparent his career was winding down. No plays are attributed to him after 1613, and it was around this time that he moved permanently back to Stratford. Then, in 1616, he died. He was 52 years old. Shakespeare is buried at Trinity Church in Stratford, where his birthplace and house are also preserved. In 1623, members of his company published the First Folio, named such because of the size it was printed at. This was the first collection of Shakespeare’s plays ever published, with many of the plays having never been published before this date. (As You Like It is one such.) The First Folio also included an engraving portrait of Shakespeare and an introduction by Ben Jonson, another celebrated playwright. It reads thus:

This Figure, that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut;

Wherein the Graver had a strife

with Nature, to out-do the life :

O, could he but have drawn his wit

As well in brass, as he hath hit

His face; the Print would then surpass

All, that was ever writ in brass.

But, since he cannot, Reader, look

Not on his Picture, but his Book.

The engraving of Shakespeare included with the First Folio.

The reconstruction of the Globe Theatre in London’s Bankside neighborhood. The Globe was the home for Shakespeare’s acting company, and where his plays were all likely performed. Today, the new Globe produces a full season of Shakespeare every year as well as a few new works, following the idea that the original Globe would have produced new work as well; for all of Shakespeare’s plays were new works in their day.

The wrestling match from Chicago Shakespeare Theatre’s 2021 production.

The cast of Dallas theatre company Fair Assembly’s 2023 production.

The cast of the RSC’s 2023 production on their “rehearsal room” set.

Production History

Orlando and Rosalind reunite at the end of the Globe’s 2023 production.

Still curious about the production history?

As You Like It falls squarely in the middle of Shakespeare’s career, with estimates placing the first performance somewhere between 1598-1600. It was likely one of the first plays performed in the Globe theatre, which was completed in 1599. The play was entered into the Stationers’ Register in 1600, which protected its copyright and meant that the play was not published until it was included in the First Folio in 1623.

Following the Restoration, no performance is recorded until 1723 at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. This was considered a sort of revival, but given the sentimental tone of most theatre at this time, the play was heavily adapted with lines taken from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Much Ado About Nothing. Character fates changed dramatically, and the wrestling match at the top of the show was transformed into an elegant fencing match, mirroring the sensibilities of new upper-class audiences. The script endured several more changes throughout the Baroque and Victorian eras, with emphasis placed on the pastoral setting, made more and more realistic through innovations in scene technology. Victorian productions in particular focused on elaborate staging, detailed backdrops, and additional music. A production in 1907 used real plants carted in weekly to create the forest atmosphere.

Extremely realistic scenery became the norm for productions of As You Like It, continuing into the present day. Modern (post-1950) realist productions tend to be produced on outdoor stages and among real forests. Modern productions also tend to play with setting more often than Victorian productions, choosing interesting time periods and locations to offer distinct commentary. For example, the National Theatre of the UK produced an all-male production in 1967 with futuristic staging. Minneapolis’ Tyrone Guthrie Theatre set the play in the aftermath of the American Civil War in 1966, and in 1985 the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production had no trees—blurring lines between court and forest.

Modern productions have also had to compete with film for spectacle. Laurence Olivier’s first screen role was as Orlando in Paul Czinner’s 1936 film adaptation, where critics praised the perfectly pastoral scenery and the levity of the script, adapted by J.M. Barrie of Peter Pan fame. But what film adaptations gain in realism they often lose in liveliness. Theatre offers a chance for audiences to connect more directly with the amusements onstage. Paradoxically, the emotions conveyed in theatre feel more real despite the setting being manufactured.

Recent productions of As You Like It include Chicago Shakespeare Theatre’s 2021 production set in the 1960s and featuring the music of the Beatles. More recently, Fair Assembly in Dallas, TX staged a pared-down production of the play in order to pull focus back into the text. Played in the round with minimal costumes and almost no set, the skilled actors of this production highlighted the specific words and actions of Shakespeare. Two productions of As You Like It ran in England this past summer, one at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford and one at the new Globe in London. The Statford production was a reunion of sorts, with the cast having previously first performed the play together in 1978. This production explored age-blindness and memory as a way of reflecting on love, life, and (most notably) the “seven ages of man.” The play was produced as “unfinished,” with the set being a rehearsal room, complete with prompters onstage for when the actors forget their lines. While the actors of this production are not young, their stunning performance of young love and youthful antics reminds us that while age is a fact of life, love is as well.

The Globe Theatre’s production of As You Like It is still running, and will close on the same date that our production does. This production, like the one in Dallas, is played on a bare stage, but that is where the similarities end. The costuming here is lavish and “Shakespearean,” reaching for the ideal of Jacobean theatre that lives in our imaginations. Many of the choices made here are deliberately imaginative and playful, from the traditional jester costume that Touchstone wears to the drawn-on mustache for Rosalind as Ganymede. The message here seems to be that love is silly and fun, and we could all use a bit more of it.

Our production now joins this legacy, and as we look back we can take both caution and inspiration from the different choices others have made. In this telling of this story, we must be aware of both the history and the future: how was this play received in the past, and how will it be received now? What will our audience have to say once the epilogue is done? What sort of story do we hope to tell, and what, ultimately, will we learn?

Mythology in Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s grammar school education left him with a very good understanding of what we would now call “the classics” — myths from Ancient Rome and Greece, stories and parables from the Christian Bible, and various other tales and fables, such as those of Aesop. Shakespeare drew on all these sources to create his worlds, and his characters often allude to figures and events from these stories. Understanding the sources that Shakespeare was drawing from can help form a greater understanding of his works as a whole. To the left is a list of the allusions found throughout As You Like It, as well as what those allusions reference and how knowing that source might provide some clarity to the text.

-

From Act I, Scene 1. Orlando speaks to Oliver, saying: “Shall I keep your hogs and eat husks with them? What prodigal portion have I spent that I should come to such penury?” This is a reference to a parable from the gospel of Luke in the Christian Bible. In the story, Jesus tells of an old man whose son had taken his inheritance and squandered it, leaving him destitute, working for a stranger feeding husks to his hogs. In this story, the son has caused his misfortunes himself, but Orlando struggles to understand why Oliver has placed him into similar misfortune without cause.

-

Referenced throughout the play, firstly in Act I, Scene 3, when Rosalind decides her man’s name. Jove is the Roman king of the gods, and at this time was often equated with the Christian god in an oath. (“By Jove,” etc.) Jove is an equivalent to the Greek Zeus, who also figures in many of the myths referenced in this play.

-

From Act I, Scene 3, this is the name Rosalind chooses for herself when she puts on her male disguise. “Jove’s own page,” is the background given for the name in the scene, which is a correct, though rather short, account of the myth. The original record, from Homer’s Iliad, describes Ganymede as a beautiful mortal young man, abducted by the gods to serve as Zeus’s cup-bearer. It was thought that the gods believed him too beautiful to not be immortal, and there are some version of the myth that place Ganymede as an object of Zeus’ desire. Ganymede is also recorded as having been a shepherd boy before his abduction. In art, Ganymede has is typically depicted as young, beardless, and classically beautiful.

-

In Act I, Scene 3, Celia describes herself and Rosalind as being like Juno’s swans, “coupled and inseparable.” Here Shakespeare has merged two myths, as swans are not typically attributed to Juno. Yet swans are often considered symbols of faithfulness and love, qualities also attributed to Juno. Juno is the name for the Roman queen of the gods, wife to Jove, and goddess of young women, marriage, fertility, and childbirth, among other things. “Juno’s swans,” a phrase invented here, is likely a reference to both the idea of swans as virtuous companions and Juno as the protector of young women.

-

This phrase, from Act II, Scene 5, is a reference to the Ten Plagues of Egypt from the book of Exodus from both the Jewish Torah and the Christian Bible. This is the last of the ten plagues, when God sent an angel of death to strike down the first-born child of every house in Egypt. This event also marked the first celebration of Passover, an important Jewish holiday, when the Jews living in Egypt were instructed to slaughter a lamb and spread the blood over their doorways, so the angel of death would pass over their homes and leave their first-borns alive. This was an extremely dramatic and climactic event, and the way it is referenced in the play borders on absurd. Jaques tells Amiens that he will “go to sleep if I can; if I cannot, I’ll rail against all the first-born of Egypt.” He compares himself with this angel of death, implying he will invoke the wrath of God if he is not allowed a nap.

-

This phrase appears is a speech by Orlando in Act III, Scene 2. As he hangs his love-verses on the trees of Arden, he speaks a prayer: “Thou thrice-crowned queen of night, survey with thy chaste eye, from thy pale sphere above, thy huntress’ name, that my full life doth sway.” This is an invocation for the Roman goddess Diana, or the Greek Artemis, both huntresses and goddesses of the moon. Diana especially is a goddess of the countryside, and she is also considered a virgin goddess, thus she is also associated with youth and with young women.

-

In Act III, Scene 2, Celia reads one of Orlando’s love-verses in which Rosalind is compared with several women of mythical and historical note. She is first described as having “Helen’s cheek, but not her heart,” referencing the mytho-historical Helen of Troy. Helen was famously the most beautiful woman in all of Greece, and promised by Aphrodite to Paris of Troy. However, Aphrodite forgot to take into account that Helen was already married, and when Paris took Helen away to Troy, her husband, King Menelaus, rallied the armies of Greece and declared the Trojan War. The distinction in this line is important: because it is not clear whether or not Helen went to Troy willingly, Rosalind has only Helen’s cheek (or her beauty) and not her heart (which might be changeable).

-

In Act III, Scene 2, Celia reads one of Orlando’s love-verses in which Rosalind is compared with several women of mythical and historical note. The second of these is Cleopatra, the last queen of Egypt, famous for both her beauty and her power.

-

In Act III, Scene 2, Celia reads one of Orlando’s love-verses in which Rosalind is compared with several women of mythical and historical note. She is described as having “Atalanta’s better part,” or characteristic, but this characteristic is not specified. Atalanta is a Greek heroine known for her courage and swiftness. She features in two prominent myths: in one, she is the only woman in a hunting party sent to kill a savage boar, and she is the one to get the first hit in on the beast. In another, she is only beat at foot-racing because her opponent distracts her with enchanted apples, winning both the race and her hand.

-

In Act III, Scene 2, Celia reads one of Orlando’s love-verses in which Rosalind is compared with several women of mythical and historical note. “Sad Lucretia’s modesty” is the final characteristic attributed to her. Lucretia was a Roman noblewoman whose story features prominently in Roman mythohistory. Her “modesty” here refers to her chastity. A symbol of Roman female virtue, Lucretia was raped by a Roman prince, and after calling for vengeance, committed suicide as a final way to preserve her honor. Her death became the catalyst for the transformation of Rome from a monarchy into a republic.

-

In Act III, Scene 2, Celia tells Rosalind that she must borrow “Gargantua’s mouth” if Rosalind wishes Celia to answer all her questions with one word. Gargantua was a character, a giant, from the Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel by François Rabelais, a French author writing during the mid-1500s. Shakespeare was likely familiar with his works, as they were very popular for their time.

-

In Act III, Scene 3, Touchstone tells Audrey that he is with her and her goats “as the most capricious poet, honest Ovid, was among the Goths.” Ovid, or Publius Ovidius Naso, was a Roman poet, a contemporary of Virgil and Horace. Although his works were popular among the people of Rome, the emperor had Ovid exiled and sent to live in Tomis, a city on the edge of the Roman empire on the Black Sea. The local people there were called “Goths” by the Romans. Ovid disliked his exile, and Touchstone’s reference to this event is a sort of sarcastic joke. He is telling Audrey that he is with her as reluctantly as Ovid was in Tomis.

-

Hymen is a Greek god of marriage, specifically the god of marriage ceremony. He appears as a character in this play, presiding over the four weddings at the close of the play.

In 2012, the new Globe produced Twelfth Night as it would have been done in the early modern era: with men playing all the roles. This image is of Olivia, played by Mark Rylance, and Malvolio, played by Stephen Fry. This particular production truly highlights the absurdity present onstage when male actors are pretending to be women pretending to be men, and Shakespeare often makes reference to this absurdity in his scripts, including in As You Like It. This production is available to watch through Drama Online for those who are curious.

Clothing and Gender in Elizabethan England

In a play where the main plot device is a confusion of genders, it is reasonable to assume that clothing plays a particular role in the script. Characters often reference clothing in relation to gender, and Rosalind's remarks are among the most obvious. In Act II, Scene 4, she states: "I could find in my heart to disgrace my man's apparel and to cry like a woman. But I must comfort the weaker vessel, as doublet and hose ought to show itself courageous to petticoat."; in Act III, Scene 2: "Dost thou think though I am caparisoned like a man I have a doublet and hose in my disposition?" and "Alas the day, what shall I do with my doublet and hose?" Celia goes along with her language in Act IV, Scene 1: "We must have your doublet and hose plucked over your head, and show the world what the bird hath done to her own nest." Celia also references her specific clothing earlier in the play, in Act I, Scene 3: "if we walk not in the trodden paths our very petticoats will catch them." (Emphasis all mine.)

Consider the engraving to the top left. This is the typical dress of an upper-class man and woman of the Elizabethan era. Notice how from the waist up, their garments are very similar: fitted sleeves, lace cuffs, large ruffs, and decorative fabrics. The man’s doublet, or jacket, mimics the woman’s bodice almost exactly. Hence the specificity in the text: a man’s garment is created by both doublet and hose. Women also wore hose, or stockings, in this era, but their hose was never seen. The skirt, or petticoat, completely covered a woman’s legs and was the most obvious visual difference between the two styles of dress. Once this is understood, it is easy to imagine how a person could so easily pass between genders with a simple change of clothes. This was a common plot convention in early modern theatre: in addition to As You Like It, Shakespeare wrote cross-dressing into many of his plays, most famously in Twelfth Night but also in The Merchant of Venice, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and Cymbeline.

However, every Shakespeare play included cross-dressing originally. Before the 1660s, women were banned from performing on the English stage, and all female parts were played by young boys. The script for As You Like It addresses this as well: in Act III, Scene 2 when Rosalind as Ganymede is explaining to Orlando how she will cure him of his love, she explains how similarly boys and women behave: “At which time would I, being but a moonish youth, grieve, be effeminate, changeable, longing and liking, proud, fantastical, apish, shallow, inconstant, full of tears, full of smiles, for every passion something and for no passion truly anything, as boys and women are for the most part cattle of this colour.” This again explains why Rosalind was so easily able to convince those around her that she was a young man. Conventions of gender at the time already considered boys and women as behaving the same, so the step towards looking the same was an easy one to take. Had this convention not existed, there would be no female characters in Shakespeare at all.

“Ambitious for a motley coat”: The Role of the Fool

As You Like It contains two of Shakespeare’s most famous clown, or fool, characters: Touchstone, the court jester, and Jaques, the melancholy lord. Both characters exemplify the early modern ideal of comic wit, and among their witty and entertaining remarks lie the simple wisdom that Shakespeare’s fools are known for. Two of the most famous lines of the play are attributed to Touchstone and Jaques because of their wisdom: “We that are true lovers run into strange capers; but as all is mortal in nature, so is all nature in love mortal in folly,” (2.4) and “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts,” (2.7).

Along with their wisdom, these characters also exemplify the differences between the different types of fool present in Shakespeare’s plays. Touchstone is the classic fool — lower class (evident through both his speech and his name) — and dressed in a fool’s attire. He offers comfort and entertainment moreso than wit, as described by Rosalind in Act I, Scene 3: “what if we assay’d to steal the clownish fool out of your father’s court? Would he not be a comfort to our travel?” In contrast, Jaques is not a proper fool — he is a courtier first and foremost, and known not for his comedy but for his melancholy. As Duke Senior describes: “I love to cope him in these sullen fits, for then he’s full of matter,” (2.1). Duke Senior sees Jaques as an equal—he values Jaques’ intelligence and seeks to comfort him, even as he finds some light humor in Jaques’ unusual sorrow. But Touchstone has a power that Jaques doesn’t have, and like many other things in this play, that power comes in the form of dress.

In Act II, Scene 7, Jaques bursts into the Duke’s gathering in shambles, having met Touchstone offstage in the woods. He is delighted by the meeting, but quickly devolves into sorrow as he realizes that what made Touchstone special was that he is a “motley fool,” unlike Jaques. This word, motley, refers to Touchstone’s style of dress, the classic “court jester” costume that we now associate with places like Rennaissance Faires and Medieval Times. But this was a true style of dress for the era, and Jaques’ fixation on it can give us some clue of how important it truly was. The close of Jaques’ lament for a motley coat is thus: “I must have liberty withal…to blow on whom I please, for so fools have; invest me in my motley. Give me leave to speak my mind, and I will through and through cleanse the foul body of th’infected world, if they will patiently receive my medicine,” (2.7). Even though the Duke values Jaques’ wit, Jaques must be more careful than Touchstone not to offend. His position, though beloved, is still more precarious than that of one wearing a motley suit.

Sumptuary laws, which determined which classes could wear which fabrics, governed the dress of all those living in Elizabethan England, but motley fabrics fell outside of this authority. As such, those in motley stood outside of class boundaries, and thus had “leave to speak their minds.” A fool could not be punished for insulting a king, for example, because their position outside of the social class hierarchy protected them. Thus, just as a doublet and hose protect Rosalind from bandits on the road, the motley coat would protect Jaques from retaliation were he to insult his social betters with his wit.

Touchstone is able to get away with the insults he hurls at other characters (“Holla, you clown!” (2.4)) but Jaques cannot speak his mind, as his position as lord and courtier is solidly within class structure and therefore subject to consequence. He is lucky, however, because the Duke enjoys his melancholy and excuses what insults he may hurl while in his “sullen fits.” A different ruler (such as Duke Frederick) might not have been so kind, nor so humble.

A classic Harlequin motley suit from the mid-1600s, just after Shakespeare’s time.

An engraving of James William Wallack as Jaques in a production from the mid-1800s.

Read more on . . .

The Importance of Sheep

Until colonization and the industrial revolution, England’s main export was wool. They sold both raw fiber and finished fabric to Dutch markets in Amsterdam, and from there English wool spread across the continent, clothing everyone from farmworkers to royalty. Wool was considered the ideal fiber: strong, soft, easy to obtain and care for, warm when wet or dry, durable, fireproof, and breathable. The care and keeping of sheep was the backbone of the English enconomy for millenia; as a result, shepherds, spinners, and weavers were extremely common and extremely important professions. Yet, like most neccessary jobs, these workers were also often undervalued and dismissed. This thinking is displayed via several interactions in As You Like It, most notably the conversation between Corin and Touchstone in Act III, scene 2. But what is also evident in this play is the appreciation that many people did have for shepherding, and the understanding that people had about where their clothing came from.

As a shepherd, Corin is most occupied with ensuring his flock is healthy and breeding, as more sheep meant more fiber, and more lambs especially meant finer fiber which was more comfortable to wear and could be sold for a higher price. Young men like Silvius or William would assist Corin during shearings, which happened yearly at least. Sheep needed to be held firmly during shearing to prevent accidental nicks, and Corin would have lost that ability with age. While shepherds today are use electric clippers to shear their sheep, the shepherds of early modern England would have used blade shears, which functioned like large scissors. A shepherd who cared for their flock the way Corin does would want to make sure that their sheep weren’t cut during shearing, as injured sheep were more prone to unhappiness and illness. Additionally, blood damaged wool and rendered it unsellable.

Once the wool was removed from the sheep, it went through a multi-step process to prepare it for spinning. Sheep live outside, so freshly sheared wool is nowhere near clean enough to wear. Wool has to be scoured, or cleaned, several times, which removes both dirt and lanolin, a natural wax produced by sheep which renders their fleece waterproof. When wool was meant for outwear, it is scoured less vigorously to retain the waterproof properties. Lanolin can also be added back into wool at the end of the process. Once scoured, wool needs to be picked. This process uses wide-toothed combs to pull the fibers apart from each other, allowing to wool to be more workable when it comes to the next step: carding. Carding, or combing, uses tools similar to pet brushes to align the fibers of wool along one direction. This creates roving which can then be spun into yarn.

A young woman spinning with a drop spindle, which is spun with the hands like a top. The spindle on a spinning wheel looks identical but is held horizontally and spun via the momentum of the wheel.

A 15th-century painting of the Virgin Mary knitting a shirt. Garments can be knit flat, where the pieces of the garment are knit separately and seamed together once finished, or in the round, where they can be knit in one piece from start to finish with no seams. Collars, like the one Mary is working on here, are often knit in the round so that they are seamless.

Unshorn merino sheep. Merino wool is a finer wool, and is able to be spun into thinner yarns than other wools. Coarser wools make coarser yarns, which are consequently more uncomfortable to wear.

Raw wool before scouring. Notice the curl shapes in the wool: these are called crimps, and contribute to a specific wool’s fineness and elasticity.

Shorn sheep. This process is typically done in the early summer so that the fleece can be regrown over the fall and winter, protecting the sheep until it is no longer needed.

A shepherd using traditional blade shears on a sheep. Notice the firmness of his grip on the sheep’s head: this process does not hurt the sheep, but they do need to remain still throughout it.

While shepherding was traditionally a male-dominated field, spinning and weaving were roles typically delegated to women. In fact, the term “spinster” originally referred to a woman who made her income from spinning, which meant she was exempt from the economical pressure of marriage. Spinning involved several steps, which varied in complexity based depending on the end goal. Thicker yarn meant for knitting was easier to spin than thinner yarn for weaving, but they were fundamentally the same processes. Yarn was spun on either a drop spindle or a spinning wheel, both of which used human momentum for power. Water power was also used, but that came later, as did steam power. Modern industrial spinning machines now run on electricity for the most part, and are often almost fully automated. But many people do still practice hand-spinning, though electric spinning wheels have become common as well.

A painting of an elderly spinner. She is holding a distaff of roving in her armpit while pulling yarn with her left hand and turning the wheel with her right.

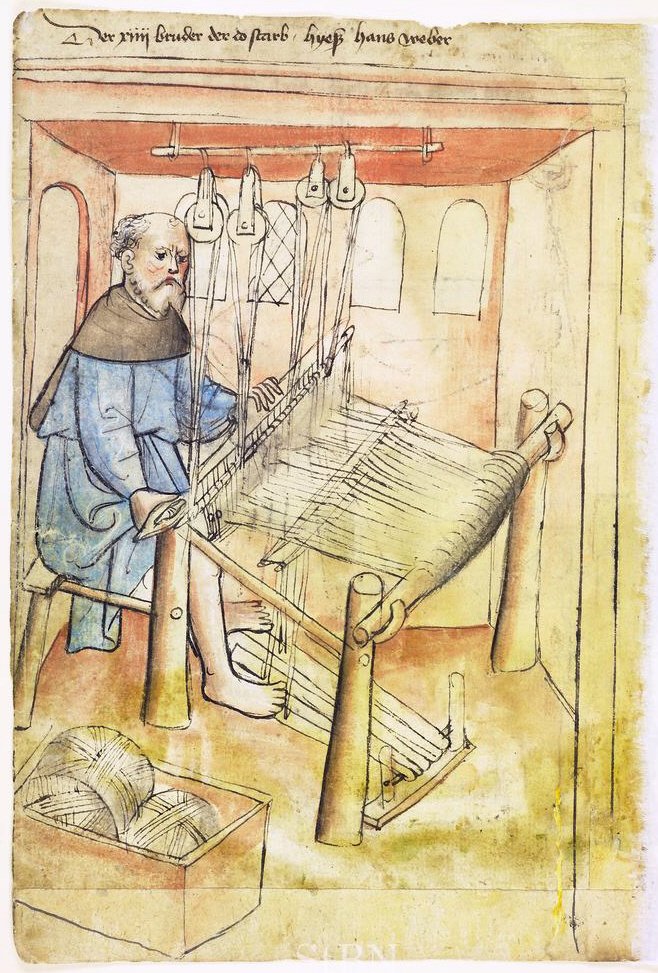

A monk weaving, from a medieval manuscript. Notice his feet at the pedals—these are what lift the threads to create the under-over pattern that turns the threads into fabric. In his right hand he holds a shuttle, in which is a spindle that unwinds as he pushes it through the threads on the loom.

To spin yarn, a spinner first needs roving, wrapped around a distaff to keep it contained, and a short length of already-spun thread to start. They tie the thread to their spindle and then hold a short length of roving against it. When the spindle spins, it will wrap the roving around the thread, creating new yarn. Then, the spinner can continue feeding lengths of roving into the spindle, controlling tension, speed, and amount of roving to achieve certain types of yarn. Yarn can be spun with a Z- or S-twist, which simply refers to the direction in which the spindle turns: clockwise or counter-clockwise. For plied yarn, where two pieces are yarn are twisted around each other to create a stonger thread, both Z- and S- twist yarns are needed. The alternating directions mean the yarns will interlock and resist unwinding.

Once spun, the yarn can then be woven or knit to make fabric. Weaving was the dominant method of fabric construction, even for garments which we now consider to be universally knit, such as stockings. Looms varied in size and complexity, which also determined what the resulting fabric could be made into. Simple lap looms were mostly used to produce scarves and stockings, while large semi-industrial looms produced the large bolts of fabric needed for skirts, gowns, and blankets. One of the other reasons why wool was so popular was because it took dye well, and looms could be modified to weave intricate patterns into the fabric. In the mid-18th century, the jaquard loom was invented, which used punch cards to “tell” the loom what to weave. This method of communication was later adapted for use in the first computers.

Knitting, another method of creating fabric, was less common but still quite prevalent. Hand knitting is quite labor intensive, and unlike weaving, it is individual work, not cooperative. Sweaters and shawls were perhaps the most common knitted garments, and were typically created by and worn by women. Knit garments also had to be made piece-by-piece, rather as one large piece of fabric, like weaving. They had to be specific to a certain person and were therefore more difficult to sell. Those who wore knitted garments were typically those with the most proximity to sheep, as they were able to use yarns that couldn’t be woven with to create useful things for themselves.

More information about wool processing can be found here:

More information about knitting and weaving can be found here:

This book, from my personal library, contains notes, illustrations, and a glossary of facts for every mention of plants in Shakespeare’s plays. I have collected the relevant notes for As You Like It here for reference.

-

From Act III, Scene 2:

CELIA. I found him under a tree like a dropped acorn.

Notes from the book: Acorn - fruit of the oak tree; the leathery outer nut/seed is cradled in a cupule (cup). The acorn can represent the weak and insignificant offspring of its mighty Oak progenitor, conversely, it is also the seed of inherent potential for the same mighty attributes.

-

From Act III, Scene 2:

ROSALIND. There is a man haunts the forest, that abuses our young plants with carving “Rosalind” on their barks; hangs odes upon hawthorns and elegies on brambles.

Notes from the book: Blackberries/Brambles - These wild berries are mentioned for their common availability both as easily edible and as thorny inhibitors in the underbrush.

-

From Act I, Scene 3:

ROSALIND. O how full of briers is this working-day world!

Notes from the book: Briers - the prickly spires on rose stems, or any “tooth’d” and thorny aspects of a plant—a variety of options are considered Briers. See also: Thorns - Any sharp-pointed spires or prickles on the stems, leaves, or heads of plants, or the plants themselves. These dangers lie in underbrush, thicket, deep woods, or a deceptive garden. Or metaphorically.

-

From Act I, Scene 3:

CELIA. They are but burs, cousin, thrown upon thee in holiday foolery; if we walk not on the trodden paths our very petticoats will catch them.

ROSALIND. Rosalind: I could shake them off my coat; these burs are in my heart.

Notes from the book: Burs - The dried up, unopened flower head [of the Burdock plant] becomes the clinging Burr, whose long, stiff bracts, with hooked tips, stick steadfastly to anything nearby; hence it often became equated with obsessive crushes.

-

From Act III, Scene 2:

ROSALIND. There’s a man…hangs odes upon hawthorns and elegies on brambles.

Notes from the book: Hawthorn/May Tree - Beloved herald of the spring, its mayflowers blooming in time for May Day fairs, and as shelter for shepherds, the tree was associated with country folk. Its abundant spikes, sometimes used as a rustic acupuncture; also [called] fairy tree for its magical powers. Its ripened red berries could make a cardiac tonic.

-

From Act II, Scene 7:

SONG (AMIENS). Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the green holly: / most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly: / then heigh-ho, the holly! / This life is most jolly.

Notes from the book: Holly - A slow-growing evergreen with attractive red berries but sharp, repelling leaves. Male and female flowers are borne on separate trees, so they need to be planted in groups to thrive.

-

From Act III, Scene 2:

TOUCHSTONE. Truly the tree yields bad fruit.

ROSALIND. I’ll graff it with you, and then I shall graff it with a medlar; then it will be the earliest fruit in the country, for you’ll be rotten ere you be half ripe, and that’s the right virtue of the medlar.

Notes from the book: Medlar - a fruit fraught with metaphor in Shakespeare. The small russet “apple” is inedible until it [appears] it has begun to rot, a fact Shakespeare mines for sexual innuendo. The fruit in French is called cul de chien (dog’s arse tree), in English slang, the “open arse” fruit. Once you’ve got that, the scenes where Medlar is mentioned become clear. It helps to see the fruit.

-

From Act IV, Scene 3:

OLIVER. Under an oak, whose boughs were mossed with age, and high top bald with dry antiquity.

Notes from the book: Oak - Renowned for its size, long life, and fine wood, the Oak is replete with metaphor: strength, reliability, durability, solidity, toughness…Oak wreaths heralded victory; with their Acorns, Oaks represented an investment in the future. Sometimes called Jove’s tree due to its mighty reputation.

-

From Act IV, Scene 3:

OLIVER. Where in the purlieus of this forest stands a sheepcote fenced about with olive trees?

Notes from the book: Olive - From Greek mythological times, the Olive was an emblem of peace. And although it didn’t proliferate as a tree in England, its fruits and oil were used and enjoyed.

-

From Act III, Scene 2:

ROSALIND. Look here what I found on a palm tree.

Notes from the book: Palm - Growing in tropical climes, the leaves or fronds were worn by pilgrims returning from the Holy Land or other religious sites. Branches were carried on Palm Sunday (Willow was often a local substitute). From ancient times, the Palm symbolized peace and victory; it still implied preeminence or honor when expressed as “to bear the palm,” “to yield the palm.”

-

From Act II, Scene 4:

TOUCHSTONE. I remember the wooing of a peascod instead of her.

Notes from the book: Pea/Peascod - Fresh young peas were a delicacy, but mostly the common kitchen garden plant was fodder, or food for common folk. Peas were easily dried for winter and rehydrated. The pod or peascod contained the individual peas (and provided ample opportunity for sexual innuendo).

-

From Act IV, Scene 3:

CELIA. The rank of osiers by the murmuring stream left on your right hand, brings you to the place.

Notes from the book: Willow/Osier - the traditional weeping willow we often picture doesn’t actually arrive on the scene until c. 1700. The Common Osier (Salix viminalis), with its slightly narrower leaves, was used interchangeably with Willow for basket weaving and garland making—wearing a Willow garland suggests grieving for lost love. In England, Willow was sometimes a stand-in on Palm Sunday for the Palm branches in church processions.

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare

Resources courtesy of The Folger Shakespeare Library

Definitions

Act I

-

(n.) a foreigner

-

(v.) dissect (a body)

-

(v.) create, as a child.

-

(v.) to leave to a person after death via a will

-

(adj.) past participle of “bind”

-

(n.) an aggressive dog or a dog in poor condition, a mongrel (insult)

-

a short, broad sword

-

(adj.) of a person, brave or heroic, (n.) a flirtatious man

-

(n.) refinement

-

(adv.) as happily, gladly

-

(v.) fail to appreciate, undervalue

-

Good Morning

-

(n.) extreme poverty, destitution

-

(adv.) perhaps

-

(n.) the purification or cleansing of someone of something, the action of clearing oneself of accusation or suspicion by an oath or ordeal

-

(n.) the outward appearance of something or someone, implies that the truth is different from the appearance

-

(v.) to make something dirty, (n.) a dirty mark or stain

-

(v.) split apart

-

(n.) a painful or laborious effort

-

(n.) a natural pigment with a yellowish-brown color, or a dark brown color when roasted (burnt umber)

-

(v.) to take a position of power illegally or by force

-

(adv.) to what place or state, to which (question)

Act IV

-

(n.) a window or part of a window set on a hinge so that it opens like a door

-

(v.) express severe disapproval of, especially in a formal statement, (n.) the expression of formal disapproval

-

a male pigeon

-

(n.) ambition or endeavor to equation or excel others, an ambitious or envious rivalry

-

a soft stone that can be easily carved in any direction

-

“God be with you”

-

(n.) an act of joining, the state of being joined, an estate settled on a wife to be taken by her in lieu of a dower

-

willow trees

-

(intj.) used to express a wish or request, “pray”

-

(n.) the area near or surrounding of a place, (British) a tract on the border of a forest, especially one earlier included in it and still partially subject to forest laws

Act IV

-

(adj.) (of a person’s legs) curved so as to be wide apart at the knees

-

(n.) a form of punishment or torture that involves caning the soles of someone’s feet

-

(n.) a woman’s chest

-

a slur used to refer to the Rromani people. Connotations of laziness and aimlessness. This word should be cut from the text (in my opinion).

-

(Latin) himself

-

(adj.) relating to marriage or weddings, (n.) a wedding

-

(n.) a witty remark

-

(n.) an expression of blame or disapproval

-

(adj.) having or showing sharp powers of judgement, astute; of weather, piercingly cold

-

(n.) possessing or showing courage or determination

-

(n.) food or provisions

Act II

-

(n.) a short bat for beating clothes when washing them

-

(adj.) attractive or beautiful

-

(n.) a citizen of a town or city, typically a member of the wealthy bourgeoisie

-

(v.) skip or dance playfully, (n.) a playful movement or a ridiculous activity, (n.) the pickled flower bud of a southern European shrub, used to flavor food

-

(n.) a cockerel, or rooster

-

(n.) a male chicken that has been castrated at a young age and fed a rich diet, then killed for its flavorful meat. A delicacy.

-

(v.) to scold or rebuke

-

(adj.) rude in a mean-spirited and surly way.

-

(n.) a shelter for mammals or birds, in this case, for sheep

-

(phrase) made of discord—compact as in “packed together,” jars as in “jarring moods.”

-

(n.) a dog-faced baboon

-

a nonsense word, defined by Jacques as a Greek invocation to call fools into a circle.

-

(n.) a sculpture or model of a person

-

(excl.) used to express disgust or outrage

-

(n.) the action or proces of flowing or flowing out, (n., medical) an abnormal discharge of the body

-

(v.) politely or patiently restrain an impulse, refrain

-

eighty (a score is twenty)

-

(v.) to make someone feel annoyed, to make sore by rubbing

-

(n). the buttocks and thighs considered together, of an animal

-

(n.) insulting, abusive, or highly critical language

-

(v.) to ring, as a bell.

-

(n.) a person, esp. a man, who behaves without morals, esp. in sexual matters

-

(v.) depict or describe in painting or words, suffuse or highlight with bright color or light

-

(v.) to cry feebly, whimper

-

(adj.) incongruously varied in appearance or character, (n.) the particolored costume of a jester

-

(n.) a Venetian character in Italian commedia dell’arte represented as a foolish old man wearing pantaloons, (n.) baggy trousers gathered at the ankles

-

(n.) the pod of a pea plant, also a term for a type of men’s doublet

-

(v.) to make amends, to compensate

-

(adj.) mangy, scabby

-

(n.) a group of lines forming the basic recurring metrical unit in a poem, a verse

-

(n.) a young lover or suitor, a country youth

-

reference to hardtack, already unappealing when fresh and likely inedible by the end of a voyage

-

(n.) the meat of a deer

Act III

-

(adj.) resembling or likened to an ape

-

(n.) a skeleton or emaciated body

-

(n.) a woman in charge of a brothel

-

(n.) obscenity in speech or writing

-

(n.) the leading sheep of a flock, with a bell on its neck, (n.) an indicator or predictor of something

-

(n.) adorned with rich clothing

-

(adj.) given to sudden and unaccountable changes of mood or behavior

-

(n.) a summary of the principles of Christian religio in the form of questions and answers

-

(n.) cicatrix, the scar of a healed wound, a scar on the bark of a tree

-

(n.) a person or thing of no importance

-

(n.) a cat-like animal, the anal excretions of which are used as a perfume

-

(n.) a rabbit

-

(n.) graceful or energetic leaps

-

(n.) a firm lustrous fabric made with flat patterns in a satin weave on a plain- woven ground on jaquard looms; a grayish red color. (adj.) made of or resembling damask; of the color damask

-

(n.) Typical Elizabethan men’s dress. A doublet is a short jacket, buttoned in the front with fitted (and often decorated) sleeves. Hose is equivalent to modern stockings, worn up to the top of the thigh and held in place with garters tied about the leg.

-

(adv.) long ago, formerly

-

(n.) a common form of painful inflammatory arthritis

-

(n.) multiples of a halfpenny, a unit of money

-

(adj.) irritating, annoying

-

(n.) a dishonest or unscrupulous man

-

(n.) a servant, (v.) to behave in a servile way

-

(n.) a type of small fruit (roughly the size of a tangerine) related to the rose, usually eaten during winter due to the fact that frost softens their tough flesh, making it like applesauce in flavor and appearance

-

(adj.) relating to monks

-

(adj.) like the moon, changeable

-

(adj.) full of danger or uncertainty, precarious, (adv.) greatly or excessively

-

(n.) a person who preaches

-

(n.) the most perfect or typical example of a quality of class

-

(adj.) occuring every day, daily

-

(n.) a small bag or wallet, scrippage is its contents

-

a week

-

sir

-

(n.) a term of address for an man or boy, typically a social inferior

-

(n.) an assembly of the clergy and sometimes also the laity in a diocese or other division of the Church

-

(n.) a person who draws and serves alcoholic drinks at a bar, a bartender

-

(n.) someone who engages in a tilt or joust

-

a year

-

why